Carlos S. Alvarado, PhD, Research Fellow, Parapsychology Foundation

It is well known that many of the early psychologists were negative about the existence of psychic phenomena, preferring to explain them via conventional principles such as fraud, suggestion, hallucination, and other ideas. Individuals such as Alfred Binet, Joseph Jastrow, and Hugo Münsterberg are examples of this tradition. In a paper I recently published I discuss a prominent example of this, namely the work of American psychologist G. Stanley Hall.

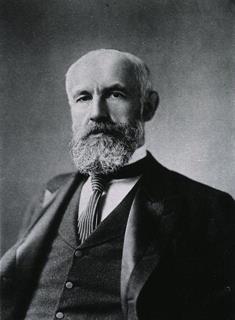

G. Stanley Hall

The paper, “G. Stanley Hall on ‘Mystic or Borderline Phenomena’ “(Journal of Scientific Exploration, 2014, 28, 75–93; available from the author: carlos@theazire.org) was not meant to be a detailed overview of Hall’s critical work, but an introduction to a little known paper of his about psychic phenomena. Here is the abstract:

“G. Stanley Hall (1844–1924) was one the most prominent of the early American psychologists and an outspoken skeptic about the existence of psychic phenomena. This article presents a reprint of one of his critiques on the topic, a little-known paper entitled ‘Mystic or Borderline Phenomena’ published in 1909 in the Proceedings of the Southern California Teacher’s Association. Hall commented on some phenomena of physical mediumship, as well as on apparitions, telepathy, and mental healing. In his view all could be explained via conventional ways such as trickery and the workings of the unconscious mind. The paper is reprinted with an introduction and annotations providing biographical information about Hall and additional information and clarification of the points he made in the paper. It is argued that Hall’s paper represents an instance of boundary-work common at the beginning of organized psychology, representing an attempt to give authority to the discipline over fields such as psychical research.”

I argue in the paper: “In addition to Hall’s unquestionable importance for the development and history of American psychology, I had several . . . reasons to choose this article. The paper is a good summary of Hall’s negative views about psychic phenomena and psychical research and represents the opinion of other psychologists at the time . . . Hall’s paper is an example of the attempts of many early psychologists to separate their emerging field from psychical research . . . I am also presenting Hall’s paper as a reminder of the importance of remembering critics and criticism in our discussions and understanding of the past developments of psychical research. This is because many historical articles published by workers in the field tend to focus on proponents of, or on defenses of, the ‘reality’ of psychic phenomena.”

Unfortunately Hall misrepresented psychical researchers several times in his paper. For example, he assumed they needed to know something about topics such as hallucinations and hypnotism. But Hall knew better than this, as he had read Gurney, Myers and Podmore’s Phantasms of the Living (1886) and he knew about Myers writings which covered much of abnormal psychology. In fact, I believe that Hall could have learned much about these topics from the psychical researchers.

Hall’s paper was also not fair to psychical researchers when he wrote: “There is almost nothing tricks cannot do, aided by skill and practice. There are many codes: for instance, reading cards can be done by two confederates, one of whom catches the heart rhythm as the toe or a crossed leg moves, and counts off the suit and the card, marking the beginning of the count by any rustle or noise of the foot, hem, sniffle, or any other sign, which the observers never detect. Probably hundreds of these tricks are well known and are found in the copious literature on this subject . . . My contention is that every investigator should know what are the resources of sleight of hand.”

But as I comment in my article: “Here, as in other writings, and in other parts of the article, Hall presents his comments without acknowledging that psychical researchers were aware of the issue of fraud and of techniques of fraud from the beginning of the movement . . . Hall had a tendency to offer advice and issue recommendations under the apparent assumption that his points had not been considered before. While this may have been true among some, such as members of the general public . . . , it did not apply to most psychical researchers.”

Consequently Hall’s writings need to be critically assessed.

On Hall’s contributions to psychology see:

Arnett, J. J. (2006). G. Stanley Hall’s Adolescence: Brilliance and nonsense. History of Psychology, 9, 186–197.

Bringmann, W. G. (1992). G. Stanley Hall and the history of psychology. American Psychologist, 47, 281–290.

Hogan, J. D. (2003). G. Stanley Hall: Educator, organizer, and pioneer. In In G. A. Kimble & M. Wertheimer (Eds.),Portraits of Pioneers in Psychology(Volume 5, pp. 19–36), Mahwa, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hulse, S. H., & Green, B. F. (Eds.) (1986). One Hundred Years of Psychological Research in America: G. Stanley Hall and the Johns Hopkins Tradition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University.

Rosenzwig, S. (1992). Freud, Jung, and Hall the King-Maker: The Historic Expedition to America (1909), with G. Stanley Hall as Host and William James as Guest. St. Louis, MO: Rana House Press.

Ross, D. (1972). G . Stanley Hall: The Psychologist as Prophet. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sokal, M. M. (1990). G. Stanley Hall and the institutional character of psychology at Clark 1889–1920.Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 26, 114–124.